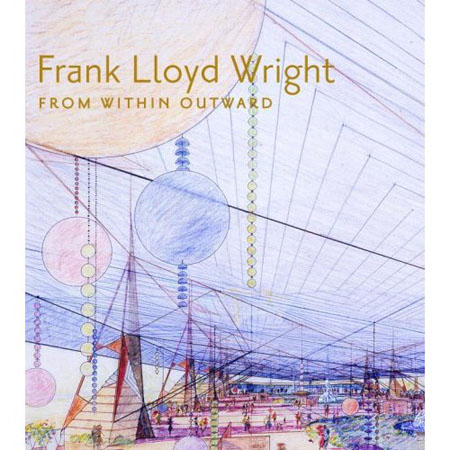

Frank Lloyd Wright: From Within Outward, with essays by Richard Cleary, Neil Levine, Mina Marefat, Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, Joseph M. Siry and Margo Stipe (Skira Rizzoli in association with the Solomon R. Guggenheim and Frank Lloyd Wright foundations, 2009)

Reviewed by Cindi Di Marzo

It is impossible to gauge which image stands tallest in the minds of his admirers (and detractors): Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) the man or his architectural designs. Wright’s towering personality, troubled personal life and rocky road to success make for a dramatic story. In 2007, journalist Nancy Horing made her debut as a novelist with Loving Frank, a fictional rendering of the most troubled period of Wright’s life, when he suffered professional setbacks; questioned the turn his life and career had taken; and left his first wife for Mamah Cheney, the spouse of a client, with tragic results.

While some Wright scholars might have raised an eyebrow at Horing’s portrayal of their heroe, her book registered spots on national bestseller lists and introduced Wright to many who knew only of his acclaimed Prairie-style homes. The bulk of Wright’s commissions consisted of private residences, but he directed much of his considerable energy and enviable imagination toward designs for public spaces. Now, 50 years after his death, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York has displayed an outstanding collection of Wright’s projects, public and private, to mark the 50th anniversary of its Wright-designed building. In association with the Guggenheim and the Frank Lloyd Wright foundations, in May Skira Rizzoli released the exhibition catalogue. No doubt, it will earn a place with other long-famed and indispensable Wright references.1

For the general reader, the catalogue provides a porthole to Wright’s brilliance as architectural philosopher. Readers will notice that many of the projects detailed in the show and catalogue were not realized. Soon into the book’s texts, they will understand, along with Wright, that architecture in the most profound sense is not about floors, walls, roofs and windows. Builders build, but Wright explored space from within outward. He aimed to create complete environments in which people could flourish. For Wright, human beings deserved organic architecture reflecting the natural setting and expressing their aspirations. Even more so, Wright promoted a connection to the wider community. Throughout his life, he wrestled with ideas for addressing this need, as well as other challenges of urban life. For example, his designs for Broadacre City, a truly sub-urban development proposed in model form in 1935, contained the flowering of ideas seeded in earlier projects. 2 In Broadacre City, Wright used design as a tool to erase barriers between city and country, organically integrate such modern necessities as cars, reinforce community ties, and protect personal privacy.

The 360-page catalogue contains 250 color and 15 black-and-white illustrations and retails for US$75. Designed by Tsang Seymour and printed by Amilcare Pizzi in Milan, the volume’s production values are impeccable. The catalogue design highlights Wright’s practice of rendering his ideas in numerous studies, perspectives and floor plans. Text placed as narration to the visual story functions almost like audio components of exhibitions; this approach is particularly effective in Wright’s case.

In five essays, Wright scholars view his legacy from different directions converging at the point of his underlying architectural vision. Margo Stipe explains his philosophy of organic interior and exterior space. Joseph M. Siry describes Wright’s designs for Unity Temple in Oak Park, IL (1905-08); the Annie M. Pfeiffer Chapel at Florida Southern College in Lakeland, FL (1938-41); Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park, PA (1953-59); Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church in Wauwatosa, WI (1956-61); and other houses of worship. Richard Cleary relates Wright’s experiences with contractors and craftsmen, including those connected with his designs for housing blocks (American System-Built and Usonian houses). Neil Levine demonstrates Wright’s quadruple block plan as the origin of the Prairie house. And Mina Marefat gives readers a tour through Wright’s grandest (and final) urban project, the unbuilt “Greater Baghdad Cultural Center.”3

Features of the Baghdad plan include an opera house, university, art gallery, museum, bazaar, fountains, bridges and a statue of Haroun-al-Rashid (the fifth Abbasid caliph, 786-809), one of Wright’s childhood heroes from A Thousand and One Nights. To connect buildings and public spaces, Wright chose the ziggurat. Like the spiral (implemented by Wright in plans for the Gordon Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium for Sugarloaf Mountain, MD, and in the Guggenheim building), the ziggurat was his way of expressing a universal and cultural geometric symbol of unity while achieving a complex architectural aim. A section of color plates follows the essays, focusing on projects in the Guggenheim exhibit. Organized chronologically, eight of the nine projects are amplified by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer; Marefat provides text for a segment on Baghdad.

Two additional titles join Frank Lloyd Wright: From Within Outward on Skira Rizzoli’s spring 2009 list. Frank Lloyd Wright: American Master, with text by Kathryn Smith and photographs by Alan Weintraub, offers readers 350 new images of Wright’s designs built from the beginning of his career through the Guggenheim, opened six months after his death. Frank Lloyd Wright, The Heroic Years: 1920-1932 by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer identifies Wright’s bold determination (and outrageous confidence) as key to his triumph over financial ruin and personal scandal during these years.

One of Wright’s most famous contributions to philosophical and practical architecture, the Guggenheim was given landmark status in 1990 by the New York City Landmark Preservation Commission; in 2005, the museum was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. With nine other Wright-designed buildings, it appears on the UNESCO World Heritage Center tentative list for designation as a national treasure.4

Looking back on his career in the pages of Frank Lloyd Wright: From Within Outward, readers may detect a nearly pre-determined destiny for Wright from his earliest days designing and building for his equally formidable family, Welsh farmers and preachers settled in Wisconsin. As such, he becomes akin to some of his heroes from childhood and beyond: Don Quixote, Haroun al-Rashid and Lao Tzu, among them. Springing from a supremely self-assured clan with roots in the stone-and-oak landscape of Wales, Wright traveled his own road, accepting it as a difficult choice. Fiercely held notions of human dignity and a democracy more God-given than political are coded into every one of his controversial designs. However one feels about Wright’s philosophy or particular built projects, as presented in this catalogue Wright is a monumental figure. From within and outward, he expressed ideals and found design solutions that cannot be ignored in our economically, environmentally and creatively challenged world.

1. Frank Lloyd Wright: From Within Outward opened at the Guggenheim on May 15, 2009, and closes on August 23, 2009.

2. Wright discussed these ideas in a 1932 article, “The Disappearing City,” published in book format (90 pages with five black-and-white illustrations) by William Farquhar Payson. Drawn from a lecture he gave in 1930 at Princeton University, the article went through many revisions. A second edition appeared in 1945, titled When Democracy Builds. Later, he rewrote and expanded the text for a final version, The Living City, published in 1958.

3. Margot Stipe is curator and registrar of collections at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in Scottsdale, AR, and Spring Green, WI; Joseph M. Siry is professor of art history and American studies at Wesleyan University in Middletown, CT; Neil Levine is a professor of the history of art and architecture at Harvard University; Mina Marefat is an architect practicing in Washington, DC, and a former senior architectural historian at the Smithsonian Institution; and Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer is director of archives at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

4. The 10 buildings being considered include the Guggenheim Museum; Taliesin, Wright’s home in Spring Green, WI; and Taliesin West and studio in Scottsdale, AZ, which serves as the headquarters of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.