The Grand Manner by A.R. Gurney

Directed by Mark Lamos

Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater, Lincoln Center, New York City

June 2-August 1, 2010

Reviewed by Cindi Di Marzo

American playwright A.R. Gurney’s work immerses audiences in Northeastern WASP culture. Much of his material draws from his background in this milieu. Born in Buffalo, Gurney graduated from St. Paul’s prep school in Concord, NH, then attended Williams College in Williamstown, MA, and the Yale School of Drama. While teaching at MIT, he began to write plays. In 1981, he debuted The Dining Room, a comedy of manners exemplifying Gurney’s career-spanning terrain. Like Jane Austen, Gurney understands that close readings of social microcosms yield universal truths; with ample doses of wit and wisdom, Gurney dramatizes hidden agendas and blatant pretensions. Yet barbed as his humor can be, Gurney brings an insider’s affection to his characters and their foibles.

Longtime Gurney colleague writer Romulus Linney described his fellow Yale graduate as bold and adventurous, referring to Gurney’s interpretations of theater conventions.1 For example, Gurney’s The Fourth Wall (1992), soon to be staged by TheatreWorks at The Fourth Wall Theatre in Upper Montclair, NJ, challenges the invisible barrier, or “Fourth Wall,” between actors and audience. In this play, Gurney conflates the “real” and the imagined by eliminating the fragile boundary between the stage and the seats. The Fourth Wall also expresses Gurney’s doubts about his career direction at mid-life and a playwright’s influence beyond the footlights.2

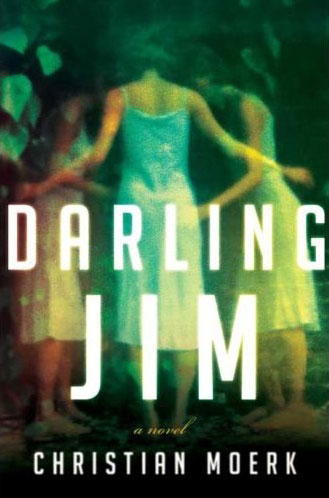

In June, Gurney’s most recent work, The Grand Manner, opened at Lincoln Center’s Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater, directed by Mark Lamos.3 A poignant, compressed drama laced with signature Gurney humor, The Grand Manner recounts a brief meeting between the young Gurney, called Pete, and a theater legend. At the time, Gurney was at St. Paul’s. His father insisted he become a physician, but Gurney toyed with pursuing a less secure career choice. In February 1948, he traveled to New York with a ticket for a performance of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra at the Martin Beck Theater, starring First Lady of the Stage Katharine Cornell.4 The Berlin-born Cornell was raised in Buffalo. Wherever she went, whatever location she chose for a residence, Cornell considered Buffalo as her home. When Gurney’s grandmother writes to Cornell to arrange a meeting with the boy post performance, Cornell readily accepts. Gurney’s father believes the visit will squelch the theater bug but, again, the boy has other plans.

Cornell’s legendary status derives from two tributaries: her never-failingly gracious, well-bred presence, and her pioneering efforts to revitalize American theater. “Grand” in the noblest sense, Cornell had every advantage that wealth and prominence affords. Unlike Gurney, whose family disparaged the theater, Cornell’s father was an amateur director and, later, managed a local theater. When Cornell put on backyard plays, he encouraged the child’s passion. By the time her mother died in 1915, Cornell had already set her sights on Broadway. With inherited money, she moved to New York. Soon Cornell’s glamorous looks and engaging personality began to win leading roles.

Dubbed “Kit” as a child because of her boyish features, Cornell cultivated interior qualities. She understood the human need to be recognized, as well as the appeal of good manners and humility. To her, audiences were not faceless crowds of ticket holders. Her words, smiles and tears were for individuals. They knew it and became devoted fans. For admirers from her hometown, Cornell’s welcome extended to backstage visits for the sharing of news and memories. She opened some of her plays in Buffalo, and whenever she appeared there while on tour, Cornell performed her most convincing role: hometown girl.

In 1921, Cornell married actor/director Guthrie McClintic. The production company they formed put little-known playwrights to work and exposed audiences to rarely performed works (including those by George Bernard Shaw and Shakespeare). They employed many actors who became legends, including Orson Wells, and they gave work to others who might otherwise have forsaken the stage. McClintic directed his wife in some of her most famous projects; for example, Candida (1924), The Brownings of Wimpole Street (1931), Lucrece (1932), Alien Corn (1933) and St. Joan (1935).

In Gurney’s flashback, Pete’s visit comes at a juncture in Cornell’s career. In her mid fifties, she feared but accepted the fickle nature of celebrity.5 Connecting her fate with the decline of live theater Cornell dreaded being pigeon-holed as a tragedienne, too “grand” to play grittier parts. A wide-eyed Pete decides to be accommodating and readily critiques her performance as Cleopatra. Too long protected from genuine criticism by her husband, her faithful personal assistant, Gert, and the notable reviewers who counted her a friend, Cornell hungers for truth. Without it, she tells Pete, theater is dead. Television and film, she cautions, capture dead performances. Even at the end of her career, when producers offered few parts, Cornell scrupulously avoided both. Roles, she believed, were created between actor and audience.

Exuding charm, Kate Burton (The Constant Wife; The Elephant Man) plays Cornell from all sides: confident professional, aging has-been, vain celebrity and humble Buffalo gal. As Pete, Bobby Steggert (Ragtime) is suitably awe-struck, the perfect blank-slate against which the others reveal their secrets. Gurney gives his ironic, quick-shot jokes to McClintic (Boyd Gaines) and Gert (Brenda Wehle). Gaines (Gypsy; Twelve Angry Men) as McClintic alternates with increasing rapidity from sophisticated producer to flawed human being. Wehle’s (Pygmalion) Gert organizes Cornell’s life with military precision, gruffly advising Pete on the ways of the world from a Broadway perspective. Hints of a magnanimous spirit and love for Cornell will endear Gert to audiences, while a pathetic seduction of Pete punctures McClintic’s pomposity.

The Grand Manner might be considered a coda to Gurney’s Buffalo Gal (2008), also directed by Lamos. Buffalo Gal examines the predicament of aging film star Amanda, who returns to her hometown Buffalo for a revival of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard. Working under a director who represents the unsung stalwarts of regional theater, Amanda begins to note uncomfortable parallels between her own life and that of her character, Madame Ranevsky. Both go home hoping to recapture a magic that exists only in memory. In reality, home is already lost to them. In the end, Amanda decides that Hollywood’s promises trump live theater’s rewards. With The Grand Manner, Gurney allows another Buffalo Gal to tell a story in which live theater is the victor.

Â

1 “A.R. Gurney” in BOMB (96/Summer 2006): http://bombsite.com/issues/96/articles/2838. Linney met Gurney in the 1950s at Yale.

2 Opening on September 24, 2010, the TheatreWorks production features Gurney’s The Fourth Wall and Tom Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound. For more information, go to: http://www.4thwalltheatre.com/index.html

3 The Grand Manner opened at Lincoln Center on June 2, 2010, and runs through August 31.

4 Cornell was so fashioned by New Yorker critic Alexander Woollcott.

5 Born in 1893, Cornell gave her birth date as 1898. She died in 1974.